Bullying awareness is important.

Recent studies have found that between 10%-50% of children are bullied on a regular basis at school, most commonly between the grades of six and ten. An online study of 50,000 teenagers by dosomething.org found that 80% of teenagers witness bullying daily.

Even when children are bystanders to aggression, they often report feeling unsafe and worried within the school environment.

When children experience the effects of bullying, they are more likely to have symptoms of anxiety, depression, and somatic concerns, including headaches, vomiting, skin problems, and stomachaches.

The damage from bullying can last a very long time.

A study published by the American Journal of Psychiatry (April, 2014) found that the impact of bullying can last long into adulthood. In fact, people who reported being bullied between the ages of seven and eleven are at increased risk for anxiety and depression at age forty-five, which is over three decades later. Another recent study found strong evidence that bullying increases the risk of severe mental health symptoms, like psychosis, in adulthood (Wolke, 2012).

So what can we do to decrease bullying, as well as the impact of bullying on our children?

If you have a school-aged child or teen, know your child’s school’s bullying policies.

Ask to see them in writing if they aren’t provided to you or available on-line. By law, if your child’s school receives state or federal funding, they are required to have a bullying policy in place. If the policy isn’t clear in the materials provided to you, ask your school principal or guidance counselor about them.

Talk to your children about how not to become a bully.

More than once. Discuss and model compassion towards others. Also, explain how words and actions can hurt people for a long time. It will also be important for you, as a parent, to be a good role model. Be kind to others, handle disagreements with assertiveness and respect for the other person’s feelings, rather than aggression. If there is evidence of bullying on the news, use these as opportunities to discuss them with your child, explaining your values and why you have those values. It is also okay to take a break from the news media, television, or movies if things are particularly heated, aggressive, or violent.

Make sure your child knows what to do if she is bullied.

Don’t assume she has been taught this at school, or that what she’s been told at school is enough to be helpful. Encourage her to talk to you about any bullying she’s on the receiving end of or is a witness to. Ask her regularly if she feels she’s being treated, or has seen others be treated, in mean or unkind ways. It is okay to be persistent.

Role-play with your child.

Practice responding to verbal baiting or teasing through role-play. Teach him how to resolve conflict in a non-aggressive way. For example, act out a scenario where you (or your child) pretends to be the bully in the schoolyard. Model how to look the bully directly in the eye and tell him firmly to stop it, and then walk away. Then, have your child practice. When your child is ready, you can also use siblings or friends to help serve as role-model assistants. Also, review with your child who safe people are at school, as well as when and how to ask for help (particularly in problematic situations or environments), and to report bullying.

Teach your child to be a helpful by-stander.

Encourage them to get an adult if another child needs help. Review with your child how to help a peer. Most times, this means telling a trusted adult at school or talking to you about it. But, it also means being able to come forward, rather than look away, when something scary, uncomfortable, or “not right” is happening to another student. Furthermore, it is very important to teach your child not to keep secrets if bullying or safety is involved. Explain that by helping in this situation, they are also helping other children.

Seek help for your child, if needed.

Professional therapy with a child psychologist or psychotherapist trained to work with children can be very helpful for children or teens who are sad, anxious, or scared. Having a trustworthy person to validate their feelings, teach skills, and help interface with school can be invaluable in these situations.

Meet with the school.

If your child has been bullied, ask to meet with the school’s principal in person. Avoid emotionality, and describe the incident as calmly as possible, explaining what happened to your child.

If your child has been bullied, and you have met with the principal, follow-up with your child’s school to make sure they took action. Even though many schools say they have a zero-tolerance policy, research tells us that many schools still fail to address bullying according to their policies. If you don’t get results with the school principal, contact the superintendent, and let the principal know you’re doing it.

Know your state and federal laws on bullying.

You can check online at www.stopbullying.gov for federal policies and your state’s laws on bullying. Mention these policies in your communications with the principal and superintendent.

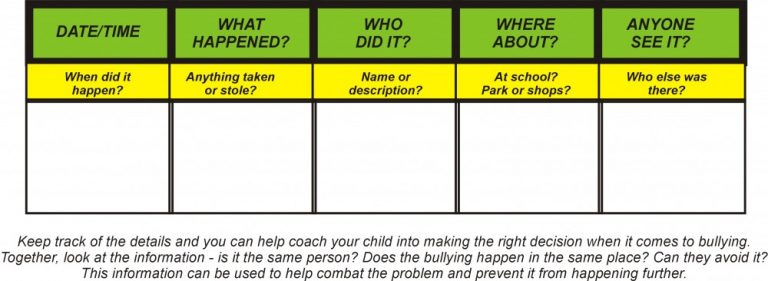

Document your interactions with the school, including dates, times and people that you talked to.

Bullying is a serious problem, and only by working together with children, schools, and families can we decrease it. If we teach our children that they are important and deserve to be listened to and treated with respect, these trends may reverse themselves. However, it will require bravery, integrity, and courage on all of our parts.

![]()